Bishop Djomo said that there are few opportunities in Tshumbe for bright young people who finish secondary school. He decided to remedy the situation by creating a university, the Université de Notre Dame de Tshumbe.

How, I asked him on July 18 as we drove to the university on the outskirts of Tshumbe, is it possible for anyone to create a university today? Difficult, said the bishop, but not impossible. The Congo government gave his diocese the land. It also pays the salaries of the professors whom the bishop recruits from the universities of Kinshasa. So the bishop’s real challenge is to raise the money to construct the buildings — and that is what he has done, constructing eight buildings around a central quad.

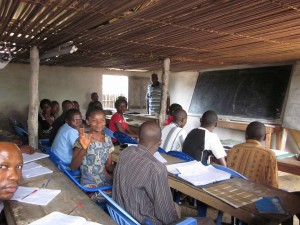

We visited the biochemistry classroom. The professor, a middle-aged man educated in Kinshasa, was lecturing in front of a blackboard. Students were sitting on plastic chairs before long tables, taking notes. There were no audio visual aids or laptops. The only concession to modernity was a fluorescent light. But students were learning about the buildup of complex molecules and the change in substances to gain energy — so that they could apply the knowledge to medicine, nutrition, genetics, and agriculture.

Bishop Djomo took us to see university’s generator — a large gasoline-powered motor — and to another nearby construction site. There workmen were building a second kiln for firing bricks that had been molded from the local clay. The bishop pointed to a ridge top, about a mile away, where the diocese was constructing a center for formation. He said that he would also build a bridge across the valley so that visiting professors could stay at the formation center and walk to the university. That evening we went to bed early, so that we could make the next day’s trip to Emungu.